Medicine is a social science, and politics is nothing but medicine on a large scale.

Rudolf Virchow, 1848

Pandemics put pressure on the societies that they strike and make visible latent structures that might otherwise remain invisible. They provide a critical perspective for social analysis and reveal what really matters to a population, whom this population truly values. In occupied Palestine, the COVID-19 pandemic intervenes in both the history and the present of dispossession, disposability, ethnic cleansing, encampment, and confinement. The pandemic reveals this history of state violence and racism against the Palestinians and their erasure while also exacerbating these processes.

Medicine urges us to understand emerging infectious diseases in terms of an interplay between pathogen, host, and environment.1 Here, I will try to explore the human actions that have crafted the host and environment in Palestine, where the struggle with the emerging pathogen will soon take center stage. A theatrical, televised spectacle of death will be produced, with bodies counted by the day, while a long, non-theatrical, carefully engineered, and often ungrievable process of larger-scale death-dealing unfolds off-scene, in health disparity reports and colorful human rights organization newsletters.

Occupied, besieged, and fragmented, the Palestinian population living in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip relies on a complex network of private and public healthcare providers, including the Palestinian Ministry of Health (MoH), the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), local and international NGOs and, when permitted, Israeli hospitals. Such arrangements result in health services that are inaccessible, delayed, unequal, and mediocre at best, services whose failures produce unnecessary and avoidable suffering, disabilities, and deaths. These fragile services are tested with each cycle of Israeli warfare, and they are now being pushed to their limits by COVID-19.

Healthcare providers in the occupied West Bank and the Gaza Strip were puzzled when the online dashboard hosted by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (one of the most visible tools used to track the spread of COVID-19) changed its designation for the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. At first listed as “Palestine” (March 5), these were subsequently called “Occupied Palestinian Territories” (March 10). Then the entry was removed altogether and merged with the Israeli figures (March 11). This second change literally erased Palestine from the map. Critical responses from the independent human rights organization Al-Haq and the Public Health Department of Birzeit University, both located in the occupied West Bank, and the spread of the hashtag #PutPalestineOnTheMap on social media prompted the CSSE to reclassify the infected area as “The West Bank and Gaza” on March 26. Still, this third attempt at classification fails to adequately acknowledge Palestine and its people, further entrenching the ends of Israeli colonial occupation and naturalizing the history of dispossession that has come to shape Palestinian geographies.

Zionist forces expelled the vast majority of Palestinians from their homeland in 1948, evacuating them to several dumping grounds in the newly created geographical units of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, which Israel would then militarily occupy in 1967. From this point forward, Israel has continuously confined and exploited these spaces, from the closure imposed on the West Bank in the 1990s, which birthed a regime of checkpoints and permits, to the siege imposed on Gaza since 2007. Meanwhile, and on the other side of the border, a small minority of Palestinians succeeded in remaining in place after the 1948 war, and were consequently granted citizenship in the new Jewish state. This new state would, however, subject this minority population to various forms of surveillance, mutilation and erasure.

The population, public health literature argues, is people living in (i.e., populating) a particular place, or alternatively a “mating pool”. Palestinian bodies were, and continue to be, subjected to colonial practices of transfer that prevent them from populating a particular place. A complex network of checkpoints, walls, and laws prohibiting family reunification has also made “mating” a risky challenge. As a result of British mandate and later Israeli state control, Palestinians have come to be negatively defined according to what they are not. Since the Balfour Declaration of 1917, Palestinians were recast as “non-Jewish communities,” lacking political identity or territory. Unlike future newcomers to their land, they were not granted entry into the newly-synthesized category of the “People of Israel.”

The very existence of the Israeli settler project is premised on the “mass transfer” of clusters of people. As the settler project continues to expand, claiming new territory and welcoming newcomers into its “mating pool,” it continuously redefines the People of Israel and redraws the borders of Israeli sovereignty. Through these processes, it engineers distinct—yet somehow similar—realities that confine Palestinians—as hosts —within degrading Palestinian-built environments, where they will struggle against the COVID-19-pathogen. Such fragmented enclaves become “the dumping grounds for the undisposed of and as yet unrecycled waste of the global frontier-land.”2

According to Lorenzo Veracini, Palestinians living in Israel have been formed as a result of different modes of transfer: (1) first, a conceptual transfer from “Palestinian” to “Arab,” where the latter is a broad, unspecified, and extra-territorial category suggesting that Palestinians come from elsewhere and nowhere in particular; (2) second, a transfer by assimilation in which Palestinians are “uplifted” to the status of “Israeli Arab citizens”; and, (3) third, a multicultural transfer in which Palestinians become part of the “multicultural nation,” together with their fellow citizens who are of Russian or Ethiopian descent.3 Like other indigenous populations in settler colonies, Palestinians within Israel became landless peasants, crowded within condensed enclaves of radicalized poverty. They suffer from shorter life expectancies and a much higher risk of diseases like diabetes, hypertension, and ischemic heart disease. This crowding, along with deficient access to healthcare facilities, predisposes Palestinians to much higher rates of morbidity and mortality from COVID-19. For comparison, indigenous populations in the Americas and the Pacific had mortality rates that were three to six times higher than the rest of the population following the H1N1 pandemic in 2009.

Since the early days of the Pandemic, the Israeli Ministry of Health has barely published any instruction or updates in Arabic, thus ignoring 20 percent of Israel’s population and the 17 percent of doctors in Israel who are Palestinian. When the ministry did finally publish materials in Arabic, it released only low quality materials after a long delay. As a result, many independent and civil initiatives have arisen to fill the gap created by the state, publishing pandemic-related data, instructions, and videos in Arabic.

Meanwhile, the media celebrated the cooperation among Israeli health, military, and intelligence agencies, which culminated in the Israeli intelligence agency’s, or the Mossad’s, secretly purchasing over 100,000 coronavirus test kits from two countries with which Israel has no diplomatic relations. Next, the army launched “Operation Save Grandma” to convert hotels into quarantine facilities. Shin Bet, Israel’s domestic intelligence agency charged with surveilling Palestinian citizens, obtained authorization to use a technology developed primarily for counterterrorism in order to identify people who might have come in contact with infected patients. In addition, Rafael, the weapons development and manufacturing company, offered to provide the state with an even more developed system capable of monitoring phones to collect audio, video, texts, and locations in order to map and predict the pandemic’s spread. These measures led to much controversy in Israeli public opinion about the invasion of citizens’ privacy and the state’s policing efforts in times of crisis. Palestinian citizens in particular were far from relieved when the ultra-right-wing ex-Minister of Justice, Ayelet Shaked, declared that she would personally ensure that the electronic surveillance of confirmed COVID-19 patients would entail minimal harm.

From the early days of the pandemic, the Israeli and international media have celebrated Palestinian doctors working in the Israeli health care systems. These doctors are hard-working, law-abiding, and professional, the media says, and therefore they do not deserve to return to their homes only to have their hearts shattered by Benjamin Netanyahu’s hateful speeches. The presence of Palestinian doctors working in Israeli hospitals has been a constant theme in celebrations of these institutions and of the state as a haven of democracy, equality, and multicultural co-existence. Some of these doctors even spoke at the AIPAC conference explaining the Israeli value of helping whoever can be helped. Others become military doctors and celebrate Israel’s impressive humanitarian efforts in places ranging from neighboring, partially occupied Syria to Haiti and Brazil. How can Israel possibly be racist in light of such headlines? Several civil campaigns calling for equality and partnership in governance have even emerged, yet without addressing Jewish superiority, the Jewish character and identity of the Jewish state or the place of non-Jews therein. Why focus on such minor details when we can participate in another colonial, Zionist, assimilationist effort, this one announced in more delicate tones? Why shouldn’t Palestinians be permitted entry into the settler colonial regime after working such hectic night shifts? What is left out of these accounts in the news is the fact that the vast majority of the Palestinian population within Israel has been gradually removed from the map.

Since no treatment currently exists for COVID-19, the only effective measure is prevention through education, social isolation, and the tracking of the spread of the virus through online dashboards, updated in real time. This is of the utmost importance for Palestinians within Israel, who live in much more crowded towns with higher percentages of disease. These conditions increase the lethality of the virus. But like any form of knowledge, statistics and maps can also serve as tools for colonial violence and can further the erasure of indigenous populations, in acts of symbolic and structural violence practiced through omission, rather than commission.

The Israeli Ministry of Health published a report on March 27, 2020, that listed only thirty-eight confirmed COVID cases in Palestinian towns in Israel out of a total 3,035 confirmed cases in Israel. This figure represented around 1 percent of the cases in 20 percent of the population. Large, crowded cities like Um el Fahem (55,200 residents) and Shafa- Amr (41,600 residents) supposedly had only one patient each. Palestinians are familiar with such low percentages from land ownership (Palestinians own percent of the land in Israel) and resource allocation to municipalities and schools. When it comes to diseases, disabilities, and deaths, by contrast, Palestinian towns are usually overrepresented. Nine out of the ten towns with the highest overall mortality rate and all ten towns with the highest death rate from heart disease are Palestinian. The rate of mortality for Palestinians is two times higher for respiratory diseases, 2.3 for Diabetes and 1.8 for hypertension and brain vascular diseases compared to the Jewish population. All of which increase the risk of dying from COVID-19.

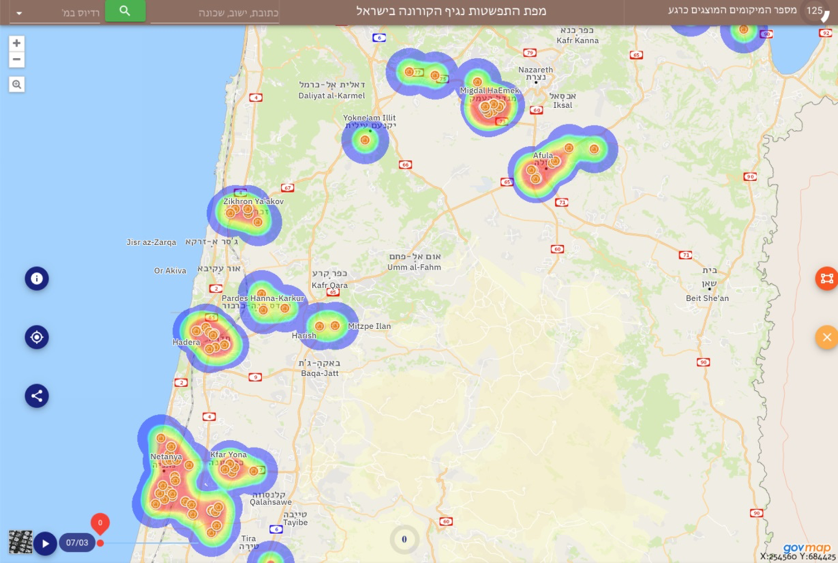

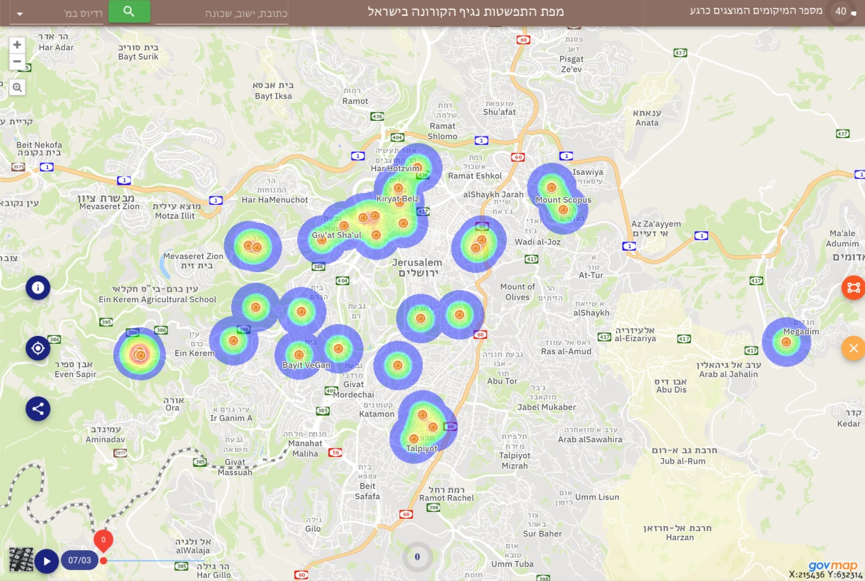

The following maps taken from the website of the Israeli Ministry of Health show confirmed cases of COVID-19. Palestinian towns are almost completely absent from these maps with zero confirmed cases.

At every step of the process of mapping the spread of the virus, Israel’s Ministry of Health has ignored the existence of the Palestinian population. This has affected everything from the location of the mobile testing points to instructions guiding who should be tested. It has led to the limited availability of Arabic-speaking call centers, a lack of tests provided to clinics in Palestinian towns and neighborhoods, and the selective updating of confirmed cases in the online dashboard.

An infectious disease specialist from Rambam hospital in Haifa announced that while the COVID-19 ward in the hospital is fully occupied, the hospital does not have any Palestinian patients, and we simply do not know how many patients have been tested or are confirmed. The list of COVID-19 patients in hospitals published by the Ministry of Health leaves a blank space for hospitals in Palestinian towns or neighborhoods like those in Nazareth and East Jerusalem.

• • •

Where there is no vision the people perish.

– Proverbs XXIX.18

Palestinians have lived under settler colonial rule for more than seven decades. Although they have been confined within a laboratory for the ongoing development of surveillance techniques, they have been subjected to various forms of erasure, from erasure of their political identity and territory in the Balfour Declaration of 1917 to the Nakba of 1948, which erased their bodies, towns, and sovereignty from the map, to continuing displacements and transfers. As these words are being written, Palestinians commemorate the 44th anniversary of Land Day, when some lives were killed, some were wounded, and some were imprisoned while trying to protest the confiscation of what remained of their lands. This new chapter in the history of the almost complete neglect of the education, screening, and mapping of Palestinians at high risk of COVID-19 might be another chapter in the history of erasure whose repercussions remain unknown.4

Share this post:

- Anneke Engering, Lenny Hogerwerf, and Jan Slingenbergh, “Pathogen–Host–Environment Interplay and Disease Emergence,” Emerging Microbes & Infections 2, no. 1 (2013): 1-7. [↩]

- Zygmunt Bauman, Liquid Love: On the Frailty of Human Bonds (Cambridge: Polity, 2003), 136. [↩]

- Lorenzo Veracini, Settler Colonialism: A Theoretical Overview (Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010). [↩]

- For further reading, please see: Rita Giacaman, Rana Khatib, et al., “Health Status and Health Services in the Occupied Palestinian Territory,” The Lancet 373, no. 9666 (2009): 837-849; Nancy Krieger, “Who and What Is a ‘Population’?: Historical Debates, Current Controversies, and Implications for Understanding ‘Population Health’ and Rectifying Health Inequities,” The Milbank Quarterly, 90, no. 4 (2012): 634–681; and Nadera Shalhoub-Kevorkian, Security Theology, Surveillance and the Politics of Fear (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015). [↩]